What if an app could guide patients to their health goals, similar to how GPS navigation directs people to a desired destination? What if we could use real-time information from smartphones and other sensors to redirect people around a disease, similar to rerouting drivers to avoid traffic? What if that real-time information included the latest medical knowledge as well as local and environmental conditions, empowering people to make healthier lifestyle choices?

By combining emerging technology with well-established cybernetic principles, this navigational approach to healthcare could soon be a reality. Just as mobile phones empowered personal communication and, combined with GPS technology, revolutionized navigation, a healthcare navigation system could empower personal health, completely transforming the current “disease care” industry into a patient-focused system of true healthcare.

The Next Revolution

The beginning of 21st century saw mobile phones leapfrogging messy and expensive wired telephone networks. Today, more than six billion people have access to mobile phones, empowering individuals to better connect with others. Furthermore, such phones are becoming increasingly smart — powerful, connected computers with numerous sensors.

Smartphones include sensors that evaluate the situation, connect to the right knowledge sources and provide actionable information when needed. For example, a smartphone’s navigation system monitors traffic and other conditions surrounding a person, finds the best route given the destination and method of transportation, and provides this information to the person. It can send reminders and automatically reroute the user as needed. We are on the verge of developing a similar system focused on health.

Currently, the industry is controlled by healthcare providers, payers (insurance companies) and employers. Patients are the least important component of the health eco-system. Yet a nexus of medical knowledge, sensors, improved computing capabilities, artificial intelligence and mobile phones has already started a major transformation in how people manage their health. Personalized, predictive, and precision-based medicine is a common focus of healthcare and technology research, and major companies and start-ups are interested in playing a major role in this space.

So, where do we start?

Disrupting the Symptom-Driven Health Cycle

Most people think of their health only when they are sick. Consider the typical process:

- People wait to see a doctor until they don’t feel good — an indication that their health state parameters are not in their normal range.

- At the doctor’s office, an assistant takes routine measurements of biomarkers — including weight, temperature, heart rate and blood pressure — and the doctor listens to internal signals using a stethoscope. The doctor also asks questions to estimate the patient’s current health state and to build and update the personal model.

- The doctor then checks vital signs and might order imaging or pathology tests.

- Combining all observations and medical knowledge, the doctor characterizes the health state as one of the known disease states and determines its level of severity.

- The doctor uses the patient’s personal model and current health state, her own medical knowledge about diseases, and general environmental knowledge to recommend corrective actions in the form of prescriptions and a regimen. These may involve medication, lifestyle or environmental changes, or some other treatment.

- The patient tries to follow the regimen. Taking medications is easy; making lifestyle changes (such as eating habits) is often more difficult. There are few good approaches for reminding people about compliance and adherence and generally no mechanisms to verify compliance.

- Depending on the severity of the disease, the doctor might want to see the patient periodically to repeat steps 2–6 as needed. The period depends on criticality: the patient might revisit the doctor’s office, be admitted to the hospital or receive critical care.

What does this process reveal? The lifeblood of our health is our data.

Data is converted into actionable information. Knowledge from different fields, particularly from the medical sciences and about the environment, is used for estimation and recommendations. Data comes in a variety of forms and is measured using different “sensors,” such as personal feelings, vital-sign measurements, imaging and pathology reports, and the doctor’s estimation based on the data collected via audio-visual-tactile senses.

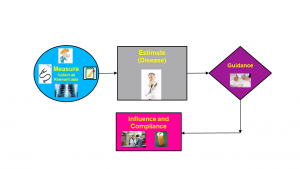

In this process, the first three steps involve data acquisition. Step 4 is state estimation, step 5 is recommendations from a professional using knowledge of the field, step 6 is compliance by the patient and step 7 is follow-up or repetition at regular intervals to manage further complications. These steps form the MEGI cycle: Measure, Estimate, Guide and Influence, as shown in Figure 1

Figure 1: The Measure, Estimate, Guide, Influence (MEGI) cycle is the norm. It has many built-in delays and components that could work more effectively if AI and data science were used with the right sensors. Another problem is that this is an open-loop system.

During the Measure step, data is collected from many relevant sources, and, using that data, the doctor estimates the patient’s health state.

The Estimation step is the diagnosis, usually in the form of a disease and its level of severity. This is currently the most important step. Once you get the right diagnosis, medical and other knowledge guides the prescriptions and regimens.

The Guide step is to personalize these prescriptions and regimens based on the specific patient and his or her situation.

For the Influence step, doctors encourage their patients to follow the prescriptions and regimens and usually request a follow-up visit, at which point the cycle is repeated. This can occur within months, weeks or days, or in severe cases, the person may be admitted to hospital for close and frequent repetition of the cycle. In extreme cases, admission to an Intensive Care Unit may be advised.

Cybernetizing the MEGI Cycle

Much of the current MEGI cycle relies on imprecise data reporting, outdated and incomplete knowledge sources and largely ineffective methods for confirming compliance. There is human involvement throughout with patients, doctors, pathologists, radiologists, and so on, and the ultimate operation is not a closed-loop system. How can we “cybernetize” this cycle — that is, apply the principles of cybernetics to gain the benefits of self-regulation?

Progress in sensors, computing and AI has disrupted many fields, but personal healthcare would be the most important area yet, given the implication for our quality of life. The financial impact is also likely to be staggering. Common sensors (accelerometers, gyroscopes, GPS, cameras and microphones) are now found in almost every smartphone, and other measurement technologies are appearing, including those that measure temperature, perspiration, heart rate, sleep, galvanic skin resistivity, blood oxygen, blood sugar and blood pressure. These advancements make cybernetic health possible, and the development of a personal health navigator that could perpetually monitor a person’s health and provide actionable guidance would result in a major disruption. Instead of treating diseases, the focus would turn to maintaining health.

Creating a Personal Health Navigator

Let’s now map the steps to a cybernetics version of the MEGI cycle.

Measurement: Using a smartphone and augmenting wearable sensors already on the market with emerging sensors that can measure many bodily functions, we could identify normal bodily parameters to determine the health state and could continuously collect these measurements. Only under very specific situations would special measurements be required.

Estimation: All those measurements could be used to estimate the person’s health using mathematical as well as medical knowledge-based techniques. This estimation could indicate proximity to a disease. The goal of estimation would be to measure the health state without assigning it to a specific disease (or some other semantic label).

Guidance To change his or her health state, the user would issue a request and the system would use medical, environmental, and other relevant knowledge sources to provide guidance in terms of lifestyle or environmental changes or medications for getting to the desired state. Guidance at each moment is similar to contextual recommendation systems, which are currently of great interest to AI researchers.

Influence: Providing guidance alone is not enough. Guidance must be situationally actionable and easy to follow. In most cases, mechanisms for nudging, incentivizing and inspiring might be required, along with subtle approaches for measuring compliance.

What is equally important is to implement this cycle on an almost continuous basis by performing all of these steps frequently to make sure that the person’s health state remains in a safe zone. This implementation rate can be directly determined by the system. The system could function autonomously most of the time but could guide the user to a nearby resource in an emergency situation.

Addressing the Challenges

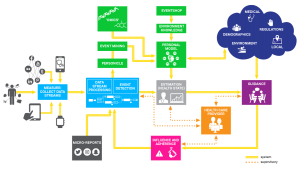

Of course, numerous challenges must be addressed before we can reap significant benefits from cybernetic health in the form of a personal health navigation system (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: A health navigator is a closed-loop system based on continuous measurement. Guidance is based on a knowledge-based recommendation engine that uses the state of the system. Healthcare professionals provide a supervisory role in an otherwise autonomous system.

Personal Models: Each individual is a unique system that must be modeled to effectively estimate the person’s health state and provide precise guidance. The personal model captures how a person reacts to different stimuli under specific conditions.

To model a person, some relatively longer-term information comes from her genome modulated by the proteome, transcriptome and epigenome and reflected in the metabolome. Lifestyle, environment and socio-economic factors also play an important role in building a model of the person. This model is not static; it changes with age and other life conditions, so model building is a dynamic process. We need reliable platforms for building these models.

Health State Estimation: Based on measurements of different biomarkers, the health state of a person must be estimated. In current medical practice, this step is the same as diagnosing a disease condition. To better understand health, more quantitative approaches require defining more health state objectives. The health state can be classified as a disease state in the same way as a combination of basic color components may be called pink or purple, but to manage colors more precisely, one must consider the primary components. A person’s health state characterizes health objectively and can be assigned different symbolic labels, like diabetes. To implement predictive, preventive and precise medicine, it is important to objectively characterize health. Disease-centric estimation looks at the health state through colored glasses and is likely to result in biased decisions.

Estimation techniques for health states will require deep biological knowledge. Eventually, we’ll be able to develop formal state-space models associated observability and controllability conditions. In the interim, we might need to build rule-based modeling techniques to implement other aspects of the complete system.

Situationally Actionable Knowledge: Prescriptions and specifications of regimens to deal with diseases are common techniques currently used in medicine. These techniques are based on available medical knowledge and other relevant knowledge sources, including environmental knowledge. Effectively, all knowledge sources are organized to find and recommend appropriate actions in a given situation.

We need to organize these knowledge sources at a finer granularity to deal with changing the health state rather than merely getting the person out of the disease state. We’ll also need to pull in different knowledge sources.

Techniques to Encourage Compliance: Once a recommendation about lifestyle and medications is made, the person is responsible for following up and complying with the specifications. As is well known, influencing people to follow the recommendations is challenging. We need to develop techniques to influence people and help them with compliance.

Exploiting Opportunities

Disruptive transformations in health have become a possibility because of the metanexus of biology, genetics, sensors, computing, and mobile devices. Progress in these areas opens up the possibility of building personal models and using them in a cybernetic framework to develop personal health navigators. Furthermore, all of the data collected for an individual could be shared and aggregated to build powerful population models related to diseases to provide recommendations in different situations.

Effectively, we have an opportunity to help people better manage their health while advancing our understanding of diseases and expediting research of potential cures. The availability of such massive amounts of individual and population-level data is unprecedented. We need to build on it, navigating society toward a healthier future.

The Institute for Future Health (IFH) at UCI is working to realize this vision. This effort will require close collaboration among researchers from health science, biomedical engineering, computer science, informatics, psychology, business, and law. Please consider joining us in our effort to build this navigational approach to healthcare, empowering individuals to improve their quality of life.